Meet the Chetti Melaka, or Peranakan Indians, striving to save their vanishing culture

Advertizement

CNA Insider

Run across the Chetti Melaka, or Peranakan Indians, striving to save their vanishing culture

There are effectually 200 of them in Singapore. There could be a few thousand more, but so piffling is known of the community that many don't know their roots. And their numbers are non all that's rare about them.

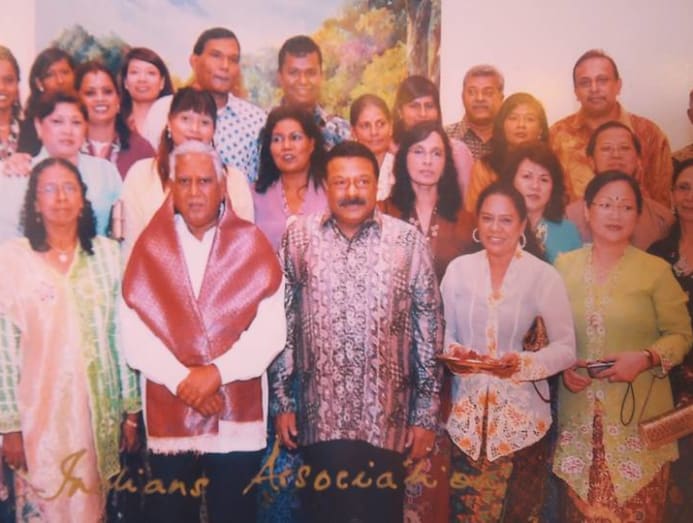

They come from Hindu roots, but honour many religions. They celebrate the Qingming festival, with an Indian twist. They speak a Malay patois, mixed with Chinese dialect and Tamil. Photo courtesy of Indian Heritage Centre.

21 Oct 2022 04:55PM (Updated: 03 Jul 2022 03:09PM)

SINGAPORE: In the home of this Hindu family, there is a Catholic altar as well equally a Buddhist altar. Here, in that location is a place for dissimilar gods and religions considering that is the philosophy this family has known for generations.

Mr Rishnaiswaren Pillay recalled how his paternal grandmother used to bring him and his blood brother to Malay shrines, chosen a keramat, to pray and give offerings.

"My grandma always told us that all religions are one and that we're all humans later on all. When nosotros cutting our easily, we have the aforementioned (coloured) blood," said the xxx-year-quondam business annotator.

"We don't let become of the Hindu practices. Information technology'due south just that … we have add-ons."

Acceptance is a word he uses, as does 71-yr-old Ponnosamy Kalastree, who is from the same community and likewise goes to unlike places of worship because "all religions preach proficient things".

The ability to accept not just different religions but also cultures is "in our Dna", said Mr Ponnosamy. And that is the Deoxyribonucleic acid of the Chetti (or Chitty) Melaka customs – the Peranakan Indians.

"I ever used to say, 'Chetti is three in ane,'" he said. "Basically nosotros're Indians, simply nosotros've embraced the Malay and Chinese culture."

The customs stretches back centuries. But its historic period-former civilisation has been eroded and is at hazard of vanishing.

There are now around 200 Chetties recorded in Singapore, and information technology was but in the last decade or and then that concerted attempts have been made to preserve their practices, from their language, food and dressing to their way of thinking.

They may be fiddling known, but the likes of Mr Pillay and Mr Ponnosamy see reasons to hope.

CHETTI-Fashion QING MING

The Chetti Melaka are the oldest Peranakans in this region, descendants of S Indians who start settled in Melaka during the reign of the Melaka Sultanate (15th to 16th centuries) and married women of Malay and Chinese descent.

The word 'Chetti' means merchant, and these pioneering traders adopted many of the local Malay and Chinese cultural influences over the years.

Every bit Mr Ponnosamy oftentimes tells his married woman Dora, a Chinese Singaporean, she is "quite lucky to ally an Indian like me considering I'm well-versed in the Chinese civilisation".

One of the nearly of import Chetti community, for instance, comes from the Qing Ming Festival, a Chinese tradition also known as the tomb-sweeping festival.

Unlike the usual Indian practice of cremation, the Chetti followed the Chinese custom of burial in the by.

And when the time came to pay respects to their ancestors, they too would visit the graves, clear the weeds and make offerings.

"You'd put the various types of food, cakes and all that … put the flowers round the whole grave, then you'd lite the joss stick," described Mr Ponnosamy, who is the president of the Peranakan Indian (Chitty Melaka) Association Singapore.

This is followed by a mixed ritual called Bhogi Parachu, ancestral prayers incorporating Indian and Chinese elements.

At habitation, the Chetti would fill banana leaves with their ancestors' favourite foods – every bit Indians would do – while lighting red candles according to Chinese prayer customs. It is a reunion day of sorts for Chetti families, "when anybody comes together".

"Parachu was a big part of my life when I was young," said Mr Pillay. "Considering it was a day, apart from Chinese New year's day and Deepavali, when we had crowds coming into our houses."

But these days, especially since his grandmother is dead, it is too great an attempt for his family to cook all their ancestors' favourite dishes, so Parachu is now a pocket-sized matter for him.

Mr Ponnosamy has likewise seen a gradual loss of this tradition as more than Chetties convert to other religions. He has relatives, for case, who exercise non desire to swallow the food offered because they are Christian, he said.

"They're dislocated between culture and religion," he added. "They don't realise that this isn't Hinduism."

DISTANCE MAKES A DIFFERENCE

One person who is able to reconcile his religious beliefs and his culture is Bible teacher Devastry Parasurama Bok, known simply as David Bok. He was born a Hindu, just becoming a Christian did non detract from his Chetti identity.

The 70-year-old permanent resident thinks, still, that the Chetti in Singapore have it tough because of that distance from Melaka, the centre of the Straits Indian culture.

1 of the festivals – the near important 1 in the Chetti culture at that place – that is all the same going stiff is the Datuk Chachar festival every May, a 12-twenty-four hours upshot dedicated to the Hindu goddess Mariamman.

She was given the name Datuk Chachar because she is known to cure ailments like craven pox (chachar in Malay). Families used to return for the festival, just hardly and then nowadays, every bit polytechnic pupil Sathyavani Balan Krishnan discovered.

When the 23-year-one-time recently visited her maternal grandmother's birthplace to sympathise her roots, she learnt that the community in the Chetti hamlet get to encounter their relatives just for a twenty-four hour period now, if at all.

And since her grandmother died when she was eight years old, "it merely felt very weird that there was this whole other tradition and culture going on that we had no idea about", she admitted.

The thing is, a lot of them looked like my relatives. The features were all and so like, so it was a chip eerie.

Indian Heritage Heart curator Nalina Gopal agreed that youngsters like Ms Sathyavani have go distanced from their roots. "Where family history hasn't been preserved, there might be a loss besides in terms of their own Chetti Melaka antecedents," she added.

One of the differences between Singapore and Malaysia is linguistic communication, and that is some other reason for the loss of the culture, every bit the Chetti traditionally speak a Malay patois infused with Tamil and Mandarin. It is called Chetti creole.

"So if one generation passes, that disappears likewise," said Mr Bok.

Mr Pillay used to speak it a bit with his grandmother. He chosen her nenek, as the Malays would. Mr Ponnosamy's girl Sheila did too, growing upwardly not realising "there were other terms that the Indians call their grandparents".

In creole, grandpa would be topeh, according to Mr Sithambaram Muragason Pillay. "The 'to' is from Malay, the 'peh' is from Chinese … and so they mixed information technology," he said.

His son, who grew upwards speaking Malay, is now hoping to relearn Chetti creole.

OF DRESS AND Food

The westernisation of Singapore has non helped, including in terms of dress, said Mr Ponnosamy.

Traditional Chetti outfits reflected the styles of the Javanese, Bugis, Acehnese, Batak and Tamil. But mostly, the men would habiliment the Malay sarong and batik shirts.

Meanwhile, the women would vesture the sarong kebaya just as the Peranakan Chinese would, only incorporating Indian elements such every bit a thali, the gilt chain worn past married women, and the pottu (dot on the brow).

These days, dressing up the traditional manner would exist possible merely on "1000 occasions", said the younger Mr Pillay, which he sees as one of the reasons it is difficult to "prove to (others) that we're proud to be Chetti".

"If you happen to (enter a temple in a kebaya), there'd exist societal pressure from other Indians in the temple who'd say, 'Why don't you use a sari?'"

When it comes to food, Chetti cuisine is a blend of Indian, Malay and Peranakan Chinese styles. But every bit both Mr Pillay and Mr Ponnosamy attest, their daily choices veer towards the Malay and Chinese options.

Mr Ponnosamy said: "If you enquire me to become to Assistant Leaf (restaurants) every now and and so, I tin't eat. Because it's too Indian. We take to accept our mixed type of food."

Sambal goreng rather than typical Indian back-scratch, added his 47-year-old girl. And definitely the kueh-kueh. She said:

When I grew older … I realised the Indians in India had a different palate for desserts. They have the laddu and other types of sweets, so it's very dissimilar.

There is no Chetti restaurant in Singapore nor even ane in Melaka, co-ordinate to Ms Gopal.

Simply the real puzzler for the community is how interracial marriages, which go to the core of their identity and are becoming more common in Singapore too, is contributing to the loss of lived culture.

"Some of them don't consider themselves to exist Chetti any more than," noted Mr Pillay.

The Chetti are "then accepting of differences" that ethnic intermarriages may cause them to be "absorbed by majority cultures", agreed Ms Gopal, 34.

But that may not exist the case for all. "The degrees are varying for each family unit, depending of class on their own personal journey," she said.

And she believes that cultural aspects such as nutrient – "which is devoid of any religious overtones" –language or fifty-fifty wearing apparel are what people tin can "reconnect with their Chetti Melaka-ness".

HOPING FOR THE Adjacent GENERATION

In terms of a physical place, in that location is a Chitty Route in Little India, indicating the customs's historical presence here. But that is now a "very small street" that few people associate with the Chetti, said Ms Gopal.

What has been a real marker for the community's revival, notwithstanding, was historian Samuel Dhoraisingam'due south volume Peranakan Indians of Singapore and Melaka, published in 2006 by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

It was launched by the late President S R Nathan, who encouraged members of the community to "have reward of the momentum and first an association", recalled Mr Bok.

By 2008, the association was registered, with Mr Ponnosamy too every bit one of the founding members. It started off by doing mainly research, talks and workshops, culminating in a 2022 symposium titled The Lost Tribe of Chetti Melaka.

"That raised awareness, and you got some Chetti Melaka coming out of the woodwork. Considering you don't know who they are, you see," said Mr Bok, himself a prime example of that point, with his Chinese looks.

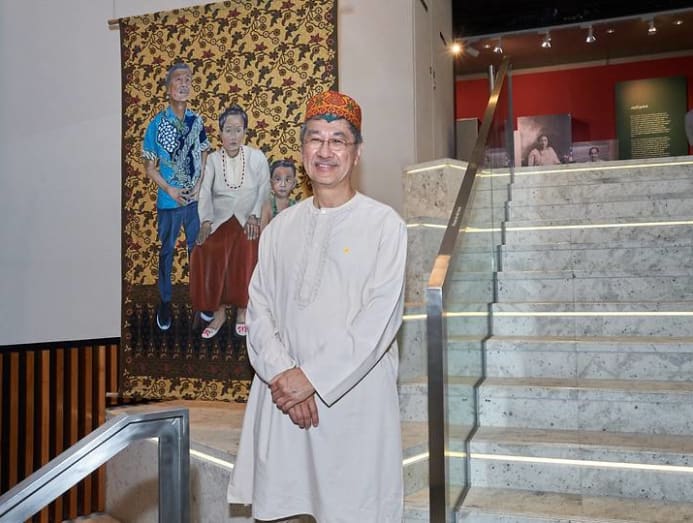

At present, on an even bigger scale, the exhibition Chetti Melaka of the Straits: Rediscovering Peranakan Indian Communities is being held at the Indian Heritage Centre, which may spark memories for anyone who might have overlooked their Chetti roots.

Mr Ponnosamy hopes so. "The hope is to encourage the younger generation to come forward," he said. "You have to do your own research, your ain family unit tree … merely patently, you'll definitely know that somehow or other yous're (Chetti)."

That was the case for Ms Sathyavani. Her father is a Malayalee Indian, only because her grandmother was from Melaka, she assumed that she was too Peranakan, though "non specifically Chetti".

Despite non practising the rituals, save for enjoying the Chetti dishes her mother would melt occasionally, she would "detest to see" the culture gone because of her generation.

"I want to exist part of the community and the youth who document this (culture), and that's something I'm looking into," she said.

However, it cannot exist just a matter of obligation, said Mr Pillay, whose mother is a Tamil Indian.

"I've a lot of friends who say that 'really my grandma is Chetti, actually my granddad is Chetti'. Merely they don't practise, or they don't visit our village," he said.

"It'due south just a selection of whether y'all want to proudly say that you're a Chetti or your roots are from Chetti."

The early signs are positive. Since the exhibition opened concluding month, the Peranakan Indian association's membership has doubled to around 200. And Mr Ponnosamy estimates that there could be as many as v,000 Chetties hither.

Just that is not the primal thing. "(The exhibition) is meant for members of the public who are Chinese, Indian and Malay," he said, stressing that the dissimilar communities must make an effort to mix to develop the Singaporean identity.

"We can't say that 'we're Indian, okay you're Chinese'. No, we desire everybody to be together … They should be one. We're one."

The exhibition at the Indian Heritage Centre is on until May v.

Recent Searches

Trending Topics

Source: https://cnalifestyle.channelnewsasia.com/entertainment/meet-chetti-melaka-peranakan-indians-striving-save-culture-hindu-219646

0 Response to "Meet the Chetti Melaka, or Peranakan Indians, striving to save their vanishing culture"

Post a Comment